The charm of a colonial city

Potosí

Potosí ![]() is located approximately 550km South of

La Paz, on the Bolivian altiplano

more than 4000 meters above sea level. The city is built at the foot of

Cerro Rico

is located approximately 550km South of

La Paz, on the Bolivian altiplano

more than 4000 meters above sea level. The city is built at the foot of

Cerro Rico ![]() (rich mount) whose pyramidal,

ochre-colored shape is beautifully framed enhanced against the deep blue sky. For centuries, the large resources

of silver and tin ores from the hill contributed to the prosperity of the Spanish empire and also to the development

and international fame of the city. Potosí has kept numerous traces of this colonial period with narrow streets and

monuments with baroque façades. A very beautiful city, rich with intense and tragic cultural and human history,

Potosí received the distinction of cultural world heritage from UNESCO in 1987.

(rich mount) whose pyramidal,

ochre-colored shape is beautifully framed enhanced against the deep blue sky. For centuries, the large resources

of silver and tin ores from the hill contributed to the prosperity of the Spanish empire and also to the development

and international fame of the city. Potosí has kept numerous traces of this colonial period with narrow streets and

monuments with baroque façades. A very beautiful city, rich with intense and tragic cultural and human history,

Potosí received the distinction of cultural world heritage from UNESCO in 1987.

The tragic history of the Potosí mines

The name Potosí probably originates from the Quechua word " potojsi" (explosion, thunder). According to the legend, in 1545 a Peruvian Indian named Diego Huallpa went to mount Sumaj Orqo (cerro rico in Quechua) to look for a group of lost llamas. While lighting a fire, he discovered by chance the precious silver-colored metal melted on the ground. The Spanish heard about this discovery and exploitation of the cerro potojsi started immediately. On the 1st April 1554, the Spaniards (in the name of Charles Quint, king of Spain) took possession of the Cerro Rico and founded the city of Potosí.

The extraction of tons of silver ore attracted rich Spanish contractors, who

started to recruit the local manpower for the exploitation of the mines. The growing appetite of the Spaniards for the metal

destroyed the life of thousands of Indians, forced to labor beyond human limits in horrendous working conditions. The mortality

rate was very high and was principally caused by sheer exhaustion, malnutrition, intoxication by the ever-present mercury vapors,

and new diseases brought by the Spaniards. The available manpower inevitably began to dwindle, and millions of African slaves

were imported into Bolivia to work in the Potosí mines. During three centuries of colonial occupation, it is estimated that some

8 million Indian and African slaves perished in the mines of Potosí.

The extraction of tons of silver ore attracted rich Spanish contractors, who

started to recruit the local manpower for the exploitation of the mines. The growing appetite of the Spaniards for the metal

destroyed the life of thousands of Indians, forced to labor beyond human limits in horrendous working conditions. The mortality

rate was very high and was principally caused by sheer exhaustion, malnutrition, intoxication by the ever-present mercury vapors,

and new diseases brought by the Spaniards. The available manpower inevitably began to dwindle, and millions of African slaves

were imported into Bolivia to work in the Potosí mines. During three centuries of colonial occupation, it is estimated that some

8 million Indian and African slaves perished in the mines of Potosí.

Mita, the mandatory work system originally instituted by the Incas, was harshly applied by the Spaniards in 1572 organizing the mining work. During this period, an important road and hydrographic network (32 artificial lagoons and aqueducts) were developed to transport water and ore to the huge hydraulic presses crushing rock to allow the extraction of the precious metal by the addition of mercury.

During the colonial period, Potosí became the largest city in South America (and also one of the largest in the world) with more than 160,000 inhabitants (i.e. comparable to Paris at that time). It is said that the Spaniards could have built a silver bridge between Potosí and Madrid with all the ore extracted from the mines. Even today, the expression "vale un Potosí" (is worth a Potosí) has remained in the Spanish language referring to anything of extreme wealth.

At the beginning of the XIXth century, the silver resources of Potosí started to decline.

The city was deserted (the population dropped to 9000 inhabitants after the war of independence). In 1866, the exploitation of tin

replaced that of silver. In the XXth century, the world at war demanded tin for the armament factories. The tin mines rejuvenated Potosí

after a long economic crisis. The mining companies were later nationalized during the political reforms in 1952.

At the beginning of the XIXth century, the silver resources of Potosí started to decline.

The city was deserted (the population dropped to 9000 inhabitants after the war of independence). In 1866, the exploitation of tin

replaced that of silver. In the XXth century, the world at war demanded tin for the armament factories. The tin mines rejuvenated Potosí

after a long economic crisis. The mining companies were later nationalized during the political reforms in 1952.

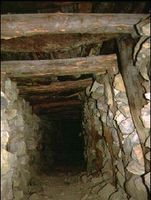

Today the Cerro Rico is nothing more than a vast perforated mountain, pierced by literally thousands of kilometers of galleries (about 10,000 galleries). The state mines are closed, with only some co-operative mines continuing to work. Only a few hundred miners continue to descend daily into the mine, despite the difficult work in precarious and unhealthy conditions that have unfortunately not changed for decades.

Historical Potosí

- La Casa de la Moneda: originally law-courts (1572), then transformed into workshops to mint money in around 1750. The museum exhibits a collection of money, artistic pieces, furniture, and clothing from the colonial period. At the entrance, visitors are welcomed by the smiling face of Bacchus (god of the wine, covered by a crown of grapes) that was hung by the French E. M. Moulon in 1865.

- Museum and convent San Francisco: the oldest convent in Bolivia (1547, rebuilt in the XVIIIth century) offers a nice panoramic view on the city. One can see the statue of Christ, which is rumored to have a beard that grows and necessitates the attentions of a special hairdresser.

- Museum and convent Santa Teresa (1865)

- The cathedral and the many churches (Belén, San Bernardo, San Martin, San Lorenzo etc...)

Visit to the active mines

- A visit to the mines of Cerro Rico is unforgettable emotional moments spent with a local guide (usually an ex-miner themselves). Via one of the 5000 entry points piercing the mountain, one arrives inside the galleries to discover the working conditions of todays miners, and attends the traditional offering rituals (challa) to the God protecting the mine (el tio). Asthmatic and claustrophobic visitors should not enter!

- The 25 colonial lagoons of Kari Kari to the South-East of the city: the hydrographic system was constructed under the supervision of Fransisco de Toledo, originally with 32 artificial lagoons, connected by the river Huana Maya bringing in water to the city and to the ore presses (ingenios). The river used to separate the Spanish zone from the native Indian zone.

The Tinku (the encounter)

Each year, in the North of the province of Potosí, the peasants of two neighboring

communities confront each other for one day using fists and foot kicks. This bloody tradition (occasionally fatal) has been enacted

since the pre-colombian period. The participants carry a typical warrior's helmet made of leather (montéra) and orange or blue tunics

(jaquetas). Official referees oversee and control the fights and the distribution of chicha (corn alcohol). At the end of the fight,

winners and losers shake hands and join together to celebrate the event with typical dances with all rivalries forgotten...

until next year!

Each year, in the North of the province of Potosí, the peasants of two neighboring

communities confront each other for one day using fists and foot kicks. This bloody tradition (occasionally fatal) has been enacted

since the pre-colombian period. The participants carry a typical warrior's helmet made of leather (montéra) and orange or blue tunics

(jaquetas). Official referees oversee and control the fights and the distribution of chicha (corn alcohol). At the end of the fight,

winners and losers shake hands and join together to celebrate the event with typical dances with all rivalries forgotten...

until next year!

The tinku is a political and social event that allows the regular release of suppressed violence between two neighboring communities - violence that may otherwise have degenerated into deadly conflict. The blood that is spilled during the fights is an offering to the Pachamama (Virgin of the earth) that ensures the community prosperity and fertility in the forthcoming harvests.